Physicality is almost always the problem with computer music: there's little as demoralising, belittling and flat-out tedious as watching a clutch of guys stare at their laptops unless something performatively diverting is also going on. So, it was a blessed relief at Cafe Oto's Intersect mini-festival when Daichi Yoshikawa picked up a tiny tambourine and proceeded to coax some very strange reverberations out of it with a contact mic, a tin can and a very careful sense of timing.

James Dunn and Chris Weaver had the same patience from sound to sound, and percussive sound palette, but didn't seem to want to hear anything they did more than once; there could have been some brilliantly off-kilter techno in there if only they could have stomached some repetition.

Thursday, 12 December 2013

Saturday, 7 December 2013

War Is Hell

Serious issue; ghastly, vacant film.

Sunday, 29 September 2013

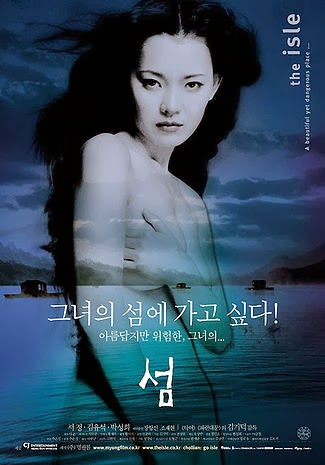

Island Mentality

This is Kim Ki Duk's bizarre isolationist universe of misogynist fishermen, smalltown prostitutes and a charged, mute female Charon figure. Animals are smacked, handfuls of fishhooks are swallowed and inserted, vengeful jealousies flare out of nowhere, attempts at tendresse are trampled in a clatter of outboard engines and scooter motors. Grey rain and light fogs obscure motive and consequence.

Song Kang-Ho as Policeman

"Tell Me Something" is the story of the unforgotten crime of sexual abuse and forced termination of pregnancy in a barely teenaged daughter, followed by the brutal and surgical murder and dismemberment of a nondescript group of the woman's wannabes and ex boyfriends.

The investigating police officer (the always charismatic Han Suk-Kyu) is even at the outset an unreliable, emotionally compromised and damaged figure, who is run over, beaten up, doused in rain and sour blood, and takes the form of a hopelessly impotent yet charmed and charming male agent of authority. His superiors are a distant and incompetent set of striding suits and stern stares.

The force of the film is a blankly terrifying, vengeful female figure, Soo-Yeon, who enlists another woman in the killing of the anonymous suitors, and then disposes of her in front of the police. when she tries to take the blame for the killings, in a pseudo-denoument to the tune of Nick Cave's "Red Right Hand" playing in a Seoul branch of Tower Records.

By the close, several dead men have had their bodies cut up, dumped in black plastic binliners in public and inadvertently discovered (one memorably in the middle of a 2 lane highway causes an ugly pile-up), the detective is collapsed outside the murderers' house, while she is on a plane to Paris.

*The most human relationship in the film, that between detectives Cho and his avuncular sidekick Detective Oh, ends gruesomely as Cho hears Oh die on the phone at the second woman's hands; the second (and obviously tomboyishly- styled) woman is then shot by Soo Yeon at Tower Records (with the gun symbolically and superfluously given her by Cho).

The theme of the bleakly comic botching of a police operation is far closer to the centre of "Memories of Murder", which is powered but burdered by being based on the true story of a notorious and unsolved sequence of serial murders. The figures of the police officers (particuarly the brilliantly intransigent, lazy but conscience-stricken Song Kang-Ho) are far too embroiled in internecine bickering, territorial disputes and work-avoidance to get close enough to the dead women to have their identity jolted.

Tuesday, 27 August 2013

New Worlds

Here are two very different routes to the same very distant destination. We are big fans of Jodie Foster, as any right thinking person would be, and I thoroughly enjoyed Neil Blomkamp's "District 9" (on a very long flight 3 years ago, in just the state of disorientation and displacement that facilitates great cinematic engagement). However, Elysium, the film, suggests that to get to Elysium, the lost paradise, the essential qualities for the traveller are firstly, a mystic prediction delivered by a wise old Nun during one's childhood, and secondly, the ability to run, shout, punch and shoot for 120 minutes The film looks brilliant; the Californian cityscapes are claustrophobic and very believably decayed , but these are punctuated by far too many master-criminal-in-his-lair-surrounded-by-screens-and-lackeys scenes to conjure a consistent sense of space.

Ellen Gallagher generates a near-effortless Paradisian dimension by creating the creatures who might populate it in a ghostly, whited-out form (her Watery Ecstatic fish and deep sea creatures emerge only barely from the paper), and by hinting at it through goggle-eyed start-charts and forbiddingly seamless black rubber canvases. The Kabuki videos, which use a rhythmically unfolding Chinoiserie of aquatic characters across a cartoon seabed, manage with a loop of half-remembered gamelan music what legions of post-production digital artists failed in Elysium: to elicit the other-worldly, the clouded paradise.

Ellen Gallagher generates a near-effortless Paradisian dimension by creating the creatures who might populate it in a ghostly, whited-out form (her Watery Ecstatic fish and deep sea creatures emerge only barely from the paper), and by hinting at it through goggle-eyed start-charts and forbiddingly seamless black rubber canvases. The Kabuki videos, which use a rhythmically unfolding Chinoiserie of aquatic characters across a cartoon seabed, manage with a loop of half-remembered gamelan music what legions of post-production digital artists failed in Elysium: to elicit the other-worldly, the clouded paradise.

Friday, 23 August 2013

Tupac and Bigger Lies

This is a documentary completely populated by people who can't be trusted, talking about things they clearly have a vested interest in. Mealy-mouthed evasiveness is a stock in trade, as is a snide and self-regarding narration. Nick Broomfield obviously knows how to walk into other people's miseries with a camera, but unerringly brings out the dead-eyed, sniggering liar in everyone he meets. A relentlessly manipulative film that I'd prefer to have never heard of.

Thursday, 25 July 2013

Bad Behaviour

Crime is hard to capture in the movies, I think. Crime is basically very dull, grimy, grimly repetitive, tedious, predictable. So film makers try to do something with it, to give us a reason to watch beyond the quickly-tiring fact of transgression.

I'd been reading about Jennifer Jason Leigh after being reminded of her deathly-chilly brilliance in Dolores Claiborne and Mrs Parker and the Vicious Circle, and heard "Rush" described in glowing terms: a forgotten gem saved from Greg Allman-guest star hell by stellar performances and compelling trajectories of hard-boiled cop to burnt-out-case. What I saw was a parade of cheesy rock'n'blues bars, good ol'boys, sets and styles that woudn't be out of place in an uninspired episode of the Dukes of Hazzard, and sequences in which Leigh and waxy co-star Jason Patric were gasping in incredulity at their own responses to their own dialogue

The fatuous faux blues soundtrack by Eric Clapton, and wincingly pointless anal rape scene only served to reinforce the sense that this was a film hopelessly out of control of its reason for being, at a very early stage.

In thankfully stark contrast, "Bad Guy" is a film whose central character is simply too priapic, convulsed with rage and robotically motivated to be captured well with the scenes and encounters of a traditionally-appearing Korean gangster flick. However that there is a period in which the mute, controlling, dumbstruck, volcanic presence of Han-Gi, staring down from his container overlooking the street where the girls are working, powerfully conjures the very specific moment in the male psyche in which the libidinal satisfactions of total control and the recoiling horror of intimacy coincide.

Han-Gi's sidekicks are more than just shellsuited goons; their sudden infatuations, impulsive stabs at honourable acting-out, and fearful loyalty have an almost religious tone of observancy.

All of which goes to show that the more precise the central psychological moment, the more robust the rest of the film will be.

I'd been reading about Jennifer Jason Leigh after being reminded of her deathly-chilly brilliance in Dolores Claiborne and Mrs Parker and the Vicious Circle, and heard "Rush" described in glowing terms: a forgotten gem saved from Greg Allman-guest star hell by stellar performances and compelling trajectories of hard-boiled cop to burnt-out-case. What I saw was a parade of cheesy rock'n'blues bars, good ol'boys, sets and styles that woudn't be out of place in an uninspired episode of the Dukes of Hazzard, and sequences in which Leigh and waxy co-star Jason Patric were gasping in incredulity at their own responses to their own dialogue

The fatuous faux blues soundtrack by Eric Clapton, and wincingly pointless anal rape scene only served to reinforce the sense that this was a film hopelessly out of control of its reason for being, at a very early stage.

In thankfully stark contrast, "Bad Guy" is a film whose central character is simply too priapic, convulsed with rage and robotically motivated to be captured well with the scenes and encounters of a traditionally-appearing Korean gangster flick. However that there is a period in which the mute, controlling, dumbstruck, volcanic presence of Han-Gi, staring down from his container overlooking the street where the girls are working, powerfully conjures the very specific moment in the male psyche in which the libidinal satisfactions of total control and the recoiling horror of intimacy coincide.

Han-Gi's sidekicks are more than just shellsuited goons; their sudden infatuations, impulsive stabs at honourable acting-out, and fearful loyalty have an almost religious tone of observancy.

All of which goes to show that the more precise the central psychological moment, the more robust the rest of the film will be.

Sunday, 14 July 2013

A Field In England

This is a limpidly brilliant hallucinatory black-and-white cinema-poem, telling the story of the arrival of 4 soldiers at a field during the dog-end of an English Civil War battle; their prosaic, pungent wrangling and traipsing, and their encounter with O'Neill, or The Devil. Magi

mushrooms are gorged on, muskets are discharged, a couple of genuinely horrifying, macabre, blackly comic sequences follow our band of brothers as they attempt to dig up the treasure that O'Neill insists is there somewhere. The exchanges between O'Neill and the Lacemaker are brutal encounters between a priapic, unswerving libidinal drive and a vacillating dutiful everyman and the strongest moments in the film.

Wednesday, 26 June 2013

The Craft of the Image

The Craft of the

Image

Putting politics

onto the screen is a business fraught with opportunities to blow the cinematic

magic, leave the audience feeling hectored-at or patronised, or deliver

something that really belongs on the television.

The House I Live

In instantly curried favour with us, sticking the very unprepossessing head of

David “The Wire” Simon on the screen at regular intervals, saying things that

really out to be coming out of the mouth of a professional sociologist or

political historian; I find it spectacularly hard to believe the film-makers

couldn’t have found a voice from outside the media-sphere. Perhaps airing

opinions on the ‘drug war’ in the US that don’t moralise or demonise is a really

dangerous business. It’s an unashamedly campaigning film that gives a fair

voice to all the interviewees; the small-town family-guy prison officer who

opens the film getting his daughters out of the house on a school day, later

gives some awe-inspiring near-Foucauldian analysis of the mechanisms of the

prison industry. Even this Lester Freamon-wannabe was gobsmacked by the

linkages drawn between the criminalization of opium smoking in California in

the early 20th century driven by fear of the Chinese,

criminalization of marijuana provoked by fear of Mexicans, and finally of

cocaine as part of the backlash against the civil rights movement. This is

public-service broadcasting in the very best sense of the term.

Pussy Riot: Punk

Prayer tried hard to do the same, but only with tired news-camera footage, and

a character ensemble of activists in a punk music group who very clearly have

no respect for the power of music: “We use any means we can to get the message

across” they might as well have said. Their message is very admirable but the

DIY anyone-can-do-it pranksterdom comes across as gauche and 6th

form for the most part. The film only really comes alive in the chaotic

courtroom scenes, during which the room feels more like a crowded zoo than

anything else.

In the same way

that a music group must have a musical language that speaks with a voice a

strong as their demagoguery to avoid the tone of a student demonstration writ

large (The Clash are the exemplars here), a movie must have a visual language

to rise above simple TV documentary: Nostalgia for the Light almost provides

too much here: The crunch in the sand of sneakers, the Zen-like pronouncements

of the astronomers (“each night, the centre of the galaxy passes over

Santiago…”), the squeaking, straining brass of the telescope, the empty

expanses of hot air and rock. The geologists, astronomers (“the past is at the

core of our work”), archaeologists and children or sisters of political

prisoners all seem to trying to tell a story the thread of which will not be

grasped in its entirety. Loss of physical remains, loss of parents, loss of a

memory which could take the form of a story all echo loudly through the

testimony. There’s a gripping sense of dried, dessicated, barely-preserved

experience, surviving almost arbitrarily in the Atacama Desert.

Saturday, 15 June 2013

Checking My Emails

There's always a relationship between the artist and their instrument, their tools, their craft. Sometimes, this relationship is entirely hidden, discrete, in the service of some other effect or dynamic. At others, this relation serves to illuminateand motivate the work.

When toxic cultural-generational forces go unchallenged however, and the artist comes to think that their relationship with their software is somehow constitutive of a performance, then there's obviously going to be trouble.

Nathan Fake (who I'd assumed might be a Nathan Barleyesque Hoxton parody of laptop musician-ry) turned out to be far worse: exactly that parody apparently unaware that because his software enables him to throw 4 ideas per 8 bars into his (obviously automated) set, he is thereby exempted from having to decide which of his ideas are any good at all.

As Chris pointed out, pithy to the max as always, "it's like a badly scratched Jamiroquai CD". I felt like I was trapped in the bedroom of someone who's bandwidth and Ableton had left them with a dizzying quantity of material and no idea whatsoever how to engage an audience with it. The floppy-fringed, head-nodding vapidity of his physical (barely) presence merely exacerbated the sense that what we were watching was a limpidly extended wank.

Jon Hopkins, thankfully, was a humble, wired, relentlessly numble-fingered pad-triggering, parameter-stretching presence, whose clipped but generous and colourful techno brought an un-reflective smile to all and sundry; his performative relationship with the computer was always one of an artist having let loose his machinery and now found himself struggling to keep up with what it was then enabled to do.

When toxic cultural-generational forces go unchallenged however, and the artist comes to think that their relationship with their software is somehow constitutive of a performance, then there's obviously going to be trouble.

Nathan Fake (who I'd assumed might be a Nathan Barleyesque Hoxton parody of laptop musician-ry) turned out to be far worse: exactly that parody apparently unaware that because his software enables him to throw 4 ideas per 8 bars into his (obviously automated) set, he is thereby exempted from having to decide which of his ideas are any good at all.

As Chris pointed out, pithy to the max as always, "it's like a badly scratched Jamiroquai CD". I felt like I was trapped in the bedroom of someone who's bandwidth and Ableton had left them with a dizzying quantity of material and no idea whatsoever how to engage an audience with it. The floppy-fringed, head-nodding vapidity of his physical (barely) presence merely exacerbated the sense that what we were watching was a limpidly extended wank.

Jon Hopkins, thankfully, was a humble, wired, relentlessly numble-fingered pad-triggering, parameter-stretching presence, whose clipped but generous and colourful techno brought an un-reflective smile to all and sundry; his performative relationship with the computer was always one of an artist having let loose his machinery and now found himself struggling to keep up with what it was then enabled to do.

Saturday, 18 May 2013

Devilish

“Les

Diaboliques” is a rare beast indeed; there’s not a moment in it that has aged

in the slightest, and the in-no-hurry-to-give-us-a-clue-or-even-a-red-herring

pacing gives it a sense of the banal, provincial and thereby the completely

believable.

There’s

an almighty reversal in the final moments, which is impressive but could have

happened in any other arrangement of duplicities, long-buried lies and

cruel-as-hell acting-out.

It’s a

common-or-garden story of casual misogyny, sexual violence, greed and small-town

jealousies and frustrations in regional France; the cinematography and set

design give the proceedings the sense of a hall of mirrors or conjuring trick.

This is fuelled wonderfully by a heavy sauce both of libidinal revenge, (“if

only he could know it was me doing it…”) and crises of identity (“at least we

will know who he is”).

Thursday, 25 April 2013

Look Now(here)

Now,

this is supposed to be one of the Great British Horror movies; a film with

genuine psychological heft and dramatic momentum. That is certainly not what I could

get hold of on the screen, where Hammer Horror Hamfisted Schlock was violently

to the fore.

Donald

Sutherland’s moustache bristled in a fake-horsehair manner. Vertigious shifts

of focus and field bring a sense of incipient nausea, for no apparent reason

other than flinging the audience through Venice as if on a bungee rope. Most of

the cast appear blotched and blotchy, as if they need more sunshine, or have

been reanimated in a brutal and abbatoir fashion.

The

dramatic horror seems to be contained within rapid and incoherent pulls of

focus and sudden lurches into eye-popping hysteria. From out of nowhere, high

heels totter and dry ice billows from unlikely garrets and cornices. It would

be funny if I hadn’t been feeling so much like vomiting.

There

appeared to be an implicit critique of an irreligious English Countrie Class,

though this was lost in the frantic and disjointed story. The whole business

had me yearning for the outrageous jolts of pace and properly objectively

unhinged points of view of a Dario Argento.

Sunday, 31 March 2013

Inside Outside

You need a big and robust idea to keep a

piece of music on the stage and under the spot light if the composers you are

celebrating are some of the most unreliable, skunked, smacked out, obtuse, and willfully

obscure. The Outsider Music Ensemble managed this the other month at Café Oto

by the simple expedient of recognizing that they themselves (the Ensemble, that

is) are anything but Outsiders. They looked quite a lot like fresh faced and

wired Music Theory MA students to me. Which meant that their vignettes by

Moondog, Cornelius Cardew and Howard Skempton were beautifully digestible and

programmed so as to be as independent-spirited as they could be,

seeing as the

same people were playing them. There was an installationary air to the thing; a

player piano spookily belted out Conlon Nancarrow and a gong solo got an airing

from a gloomy corner. They know how to make an entrance too, to a hauntingly repetitive

lovelorn chant. Inspirational, in the best way.Tuesday, 26 March 2013

Blending In

"The Conformist" was a chillingly quietly designed

film, everything undemonstrative curves and unfussy opulence. Marcello’s

trajectory through the murder of a family employee when he was a child, a

blank-eyed marriage and robotic, opiated pursuit of social and political

success is hard to look away from; its exhausted, uncomprehending finale is

thrown into sharp relief by the huge events taking place away from the screen.

In the film, the characters are barely human, driven by self-serving, servile,

pinched ideology that embeds them. There’s an unbearable relentlessness to the

progress of the plot that’s entirely right.

Tuesday, 5 March 2013

Absolute Power

Addressing authority, God, the government,

the Big Other in cinema is always a business of exposure, of the lack of

it. The spine- chilling climax of the

‘Testament of Dr Mabuse’ is an object lesson in management of the essential disappointment of power. As with Hannah

Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’, the scene of the cut-out dictatorial voice barking

into a microphone in a concrete bunker is chilling in its emptiness, its

resemblance to any lock-up garage.

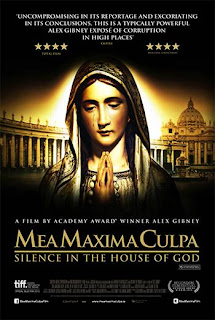

So ‘Mea Maxima Culpa’ is on very

challenging ground in its documentation of a group of men from Wisconsin, who

attempt to bring to account the Catholic priest who sexually abused them while

pupils at a school for the deaf in the 10960 and 1970s. The film- makers skillfully

elide the more general collision between the spurious ‘statehood’ of the

Vatican and its associated legal inward-looking mindset and inability to

address any ethics not centred on its own preservation. The characterfulness of

the sign language is endlessly engaging, and the commentary of the New York

Times journalist who had an inbox-ful of abuse for reporting them

sympathetically was instructive: ‘When I heard that some deaf guys from

Wisconsin were handing out photo-statted flyers outside a cathedral accusing a

priest of abusing them, I know there was a story that needed to be told’.

Incidentally, yesterday I heard John

Humphreys interviewing a senior British Catholic regarding the way in which the

church has responded to accusations of abuse; Humphreys used the word “flippant”

to describe the responses he was hearing and didn’t get contradicted or

challenged.

“No” is a far more mediated, but equally

encased telling of the story of the encounter between a socially embedded and

compromised character and the brute force of power. Gael Garcia Bernal is

obviously totally watchable on a cinema screen; using 1980s TV news film stock,

the narrative chases him through the Chilean referendum, which delivered a

decisive rejection of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. Bernal’s bemusement as

the advertising strategies he clearly sees can be brought to bear on a political

campaign, actually appear to work in the service of social goals he barely believes

in, is wonderfully acted. Bernal doesn't so much as expose power in a revolutionary way, as throw into sharp relief just how mechanical and boring power is.

Not so much as “speaking truth to power” as

“being professional in the face of power”.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)