Addressing authority, God, the government,

the Big Other in cinema is always a business of exposure, of the lack of

it. The spine- chilling climax of the

‘Testament of Dr Mabuse’ is an object lesson in management of the essential disappointment of power. As with Hannah

Arendt’s ‘banality of evil’, the scene of the cut-out dictatorial voice barking

into a microphone in a concrete bunker is chilling in its emptiness, its

resemblance to any lock-up garage.

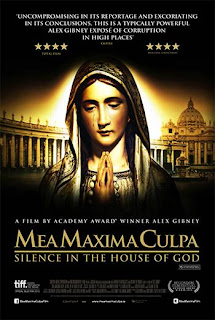

So ‘Mea Maxima Culpa’ is on very

challenging ground in its documentation of a group of men from Wisconsin, who

attempt to bring to account the Catholic priest who sexually abused them while

pupils at a school for the deaf in the 10960 and 1970s. The film- makers skillfully

elide the more general collision between the spurious ‘statehood’ of the

Vatican and its associated legal inward-looking mindset and inability to

address any ethics not centred on its own preservation. The characterfulness of

the sign language is endlessly engaging, and the commentary of the New York

Times journalist who had an inbox-ful of abuse for reporting them

sympathetically was instructive: ‘When I heard that some deaf guys from

Wisconsin were handing out photo-statted flyers outside a cathedral accusing a

priest of abusing them, I know there was a story that needed to be told’.

Incidentally, yesterday I heard John

Humphreys interviewing a senior British Catholic regarding the way in which the

church has responded to accusations of abuse; Humphreys used the word “flippant”

to describe the responses he was hearing and didn’t get contradicted or

challenged.

“No” is a far more mediated, but equally

encased telling of the story of the encounter between a socially embedded and

compromised character and the brute force of power. Gael Garcia Bernal is

obviously totally watchable on a cinema screen; using 1980s TV news film stock,

the narrative chases him through the Chilean referendum, which delivered a

decisive rejection of Pinochet’s military dictatorship. Bernal’s bemusement as

the advertising strategies he clearly sees can be brought to bear on a political

campaign, actually appear to work in the service of social goals he barely believes

in, is wonderfully acted. Bernal doesn't so much as expose power in a revolutionary way, as throw into sharp relief just how mechanical and boring power is.

Not so much as “speaking truth to power” as

“being professional in the face of power”.

No comments:

Post a Comment